Experimental research with a modified saddle tree suggests that moving the rider’s weight forward on the horse’s back improves performance. Of course, one question leads to another … but is the performance horse industry ready to accept a design change?

In a thesis offered by Garry Acuncius and Megan Cooke, these questions are explored and demonstrated.

Few people go out of their way to inflict pain on their horse. But the damage done by a poorly fitted saddle isn’t readily visible. Many horses suffer from “saddle abuse” without their owners ever realizing it. The most common symptoms of back problems are sores, but performance horses frequently show other signs of “sored” backs.

While there are thousands of bits and a myriad of new and high tech equipment coming into the equine industry, there has been very little change in saddles for over 150 years. They just seem to be accepted as they always have been. However, Garry and Megan have taken a new look. They are both accomplished and titled World Champion Cutting Horse breeders, trainers, and exhibitors. Riding a cutting horse is no easy feat. It takes core muscles most of us don’t even know we possess. It takes balance and timing way beyond what our easy trail mounts require from us.

If a horse could perform with no rider at all, his movement would be totally unrestricted. Every ounce of agility would be maintained. The saddle and rider are a necessary evil of the competition horse. A saddle is a rigid structure that connects the dynamic structures of the horse with the rider. The fit and position of the saddle (and thus the rider) affect the movement of the horse and the ability of the rider to communicate his wishes to the horse.

From this perspective, they wondered if there was a way to further “blend” with their horse. The less a rider influences a horse’s center of balance, the more freely he could move, the more potential for his highest performance level.

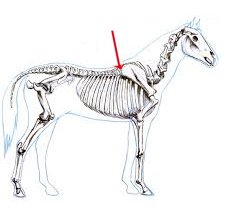

The correct balance of the rider in the saddle is important. But if we do not know the “balance of the horse”, it is impossible to make the rider and the horse coincide. Ideally, the rider’s center of balance should be over the horse’s center of balance for the least amount of interference with the horse’s performance.

The Monty Foreman school of thought believes that the saddle should be carried “all on the shoulders”. The late Monty Foreman was a horseman and clinician known for his study of the horse’s natural balance and motion. Foreman’s contention was that there is one place on the horse where he is able to carry his weight fastest at any distance, jump higher and wider, yet be in control at all speeds.

“Now if a feller wants more speed, endurance, control and better performance, shouldn’t he figure out how to ride that “carrying spot”?” Foreman once asked.

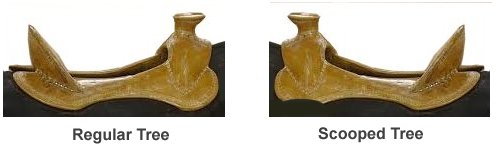

Reviews of clinical studies using computerized instruments show where the pressure points under a saddle are – where a poorly-fitted saddle contributes to poor performance syndrome – creating soft tissue pain and damage that, in turn, leads to many of the behavioral and lameness problems seen in horses in every sport. They show that excessive pressure is exerted under the front of the bars, which are usually convex in shape. Conclusion #1: This piece of new information might indicate that a concave-shaped bar is better.

In order to determine how a horse’s weight is distributed, horses were weighed at the Tarleton State University Equine Center. The average distribution was 57% on the front legs and 43% on the back legs. Saddled, regardless of rigging (3/4, 7/8, and full double), the weight distribution did not change. However, the addition of a rider sitting in the center of the saddle, as opposed to the back, can change the weight distribution to 60% in the front and 40 % in the back.

In an effort to determine the horse’s center of motion, the Texas A&M University Equine Center provided a high speed treadmill and horses for observation. The horses were marked with white spots located in 2-inch increments down from the withers on the shoulder, behind the shoulder, and on the hip. Observations indicated that the spot located in the heart girth area moved the least – implying a center of motion. The study also indicated one third less down-and-up movement in the withers compared to the hips. The down-and-up movement together with forward movement, tends to move the rider back – especially if the saddle is forward on the withers, the position preferred by the research in this study. Therefore a 3/4 or 7/8 rigging that moves the saddle forward – together with a center pocket in the saddle seat that allows the rider to stay forward – is strongly indicated.

The most common fault regarding saddle fit as it concerns the rider is a seat that is too small. This forces the rider to sit at the back of the saddle and puts excessive pressure on the horse’s back according to a 1994 Equine Veterinary Journal article by Dr. J. C. Harman, who has used computerized instruments to measure pressure points on horses.

Optimal position for the rider would be riding straight up over the heartgirth, moving in sync with the horse’s shoulder and withers and not over his back. This flies in the face of “Cutter’s Slump”, frequently explained to rider’s of Cutting Horses, who believe that sitting back on their pockets being “dragged” by rather than helping their horse is the preferred position to “get out of the way” of their horse while he does his job. This backward position puts them over the part of the horse that has the most up-and-down movement, putting much more strain on the horse’s back. It is certainly not over his center of motion suggested by the research where a rider’s weight becomes negligible in the performance equation.

Optimal position for the rider would be riding straight up over the heartgirth, moving in sync with the horse’s shoulder and withers and not over his back. This flies in the face of “Cutter’s Slump”, frequently explained to rider’s of Cutting Horses, who believe that sitting back on their pockets being “dragged” by rather than helping their horse is the preferred position to “get out of the way” of their horse while he does his job. This backward position puts them over the part of the horse that has the most up-and-down movement, putting much more strain on the horse’s back. It is certainly not over his center of motion suggested by the research where a rider’s weight becomes negligible in the performance equation.

Garry and Megan’s Theory: A performance horse saddle should be using 3/4 rigging, which necessarily moves the saddle slightly forward on the horse. The seat should not be too small for the rider to move forward and the seat should be altered to make that forward position comfortable. And, in order to make a saddle more comfortable for the horse when it is positioned higher over the shoulder, some alterations may be in order. Back to the Conclusion #1 above: A concave-shaped bar is better. If the front of the bar is scooped out, there is less gouging into the muscle bulges that run over the withers and shoulder of the horse.

To test the theory, a Dina Cutter Special saddle tree was ordered with thin bars shaped concave rather than convex under the front, upper and lower stirrup leather cuts, and 12-inch swells. Further modification included raising the seat at the cantle and lowering the pocket in the center. A 3/4 rigging and stirrups were added in order to test the tree as a saddle. This saddle tree has been ridden consistently without causing soreness in the horse or rider. Opinions of the riders was that performance was enhanced.

When the experimental saddle tree was displayed at the Tarlton State University booth during the 1998 NCHA Futurity, the theory behind the design stimulated discussion and some favorable responses, including some from traditional saddle makers. “Moved the saddle forward and the horse worked better – don’t talk about it because no one else does,” was one comment. “Can you change people who are used to riding further back even if the forward seat is better?” another asked.

The survey suggests that the deepest part of the seat should be forward, in the center of the saddle, allowing the rider to move both forward and backward in the nearly-flat saddle seat without bumping the horse by hitting either the front or back of the saddle. The study certainly indicates a need for more research on saddle fitting together with more dissemination of the information to the equine industry.

Yet, the saddle industry has almost no way to help a horse owner properly fit a saddle to their horse, no way to collate new research or to investigate new designs. In fact, the tight grip that the “good old boy” thinking has had on the saddle industry is monumental. But that might be changing. Many natural horsemanship trainers are developing huge followings. Hopefully their “out of the box” thinking, and their fearless promotion of “new” ideas will influence new saddle designs that change movement restrictions, enhance communication, and change the balance of the rider for the betterment of the horse. Garry Acuncius and Megan Cooke are certainly trying to do their part.

Appreciation must be extended to Texas A&M University, the saddle tree makers and the saddle makers (particularly John Simon of Stephenville) who assisted in this research.

Garry and Megan operate GDA Livestock in Glenrose, Texas. They are both graduates of Texas A&M University. With the modified saddle, (as of the late 1990’s when this article was first published) they had won two Palomino Horse Breeders of America world champion cutting titles, six honor roll titles, and numerous state championships. Since then the World Championships just keep coming. In 2012 they were awarded Wold Championship PTHA, Trained. Trained Sixteen Acres: all time high point leader and champion PHBA.